In real life, every woman I know would be classified as “difficult” the way my characters are. To me, to be “difficult” means to be human-imperfect, struggling with baggage from the past, responsibilities, aging, expectations, dreams. Sometimes, the word “difficult” is a code word for “bitchy.” Someone you don’t want to deal with. However, this whole concept of “difficult” women still puzzles me. “In this enjoyable novel, imperfect and at times unlikable women become lovable,” it says. Kirkus Reviews praised my most recent novel, Sisters of Heart and Snow, for this very reason. I like a nice dose of redemption in my writing. I make my characters to start out in a low place of struggle, so they have room to soar by the end. And I’d like to think I’m getting better at it. Yet though I’m “women’s fiction,” my fingers seem to be physically incapable of typing out descriptions of non-difficult women. Nor would I want to read most of his favorites. After all, my dear father-in-law, who loves thrillers where there’s lot of action and little thinking, wouldn’t want to stumble into a women’s fiction novel by accident. I’ve also found out that all these categories are useful and necessary for bookstores and librarians, so people who want this specific kind of book will know where to find it. Keep on amusing yourself with your cute little women’s fiction.”) Though some writers view the term “women’s fiction” as a pejorative or a way to make women’s writing lesser than a man’s (the equivalent of a man in a tweed jacket smoking a pipe and patting you on the head and saying, “Good for you.

I don’t mind wearing the women’s fiction badge. In addition, my books tend to focus on family drama and themes about cultural identity-not terribly different than novels categorized as “fiction” except that the main characters are female. I simply wrote the story I wanted to write, which happened to have female characters-because it was a mother-daughter story.īut then I found out that my novels are categorized as women’s fiction, generally understood to have a heroine who has some kind of emotional journey where she saves herself from a high-stakes problem, with possibly a bit of romance thrown in for interest.

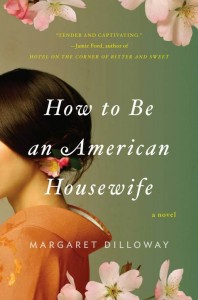

But then again, it was also a surprise that anything I wrote was “women’s fiction.” When I wrote my book, I did not think of it as being in any category. “Your characters are kind of gritty,” he said. After I sold my first book, How to Be an American Housewife, an assistant at my literary agency expressed hope that the publisher wouldn’t change me too much.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)